IMPERFECTION

You’ve got to love your mistakes.

In the 13th century the Persian poet Rumi said: The wound is where the light enters

And 800 years later, in the 20th century Leonard Cohen re-worked this idea with his lyrics: Forget your perfect offering. There is a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in.

Your challenge as an actor is to find the balance between the perfect offering and the cracks. Between precision and freedom.

When your preparation is faultless, then you can revel in ownership and enjoy the qualities of risk and wildness.

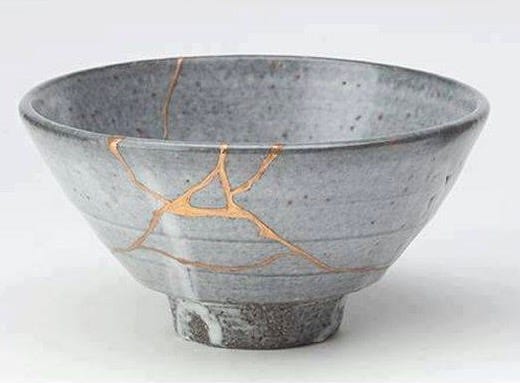

KINTSUGI

The Japanese practice of Kintsugi is a celebration of what is broken. It is the ancient art of repairing pottery with gold or silver lacquer and understanding that the piece is more beautiful for having been broken.

The tradition reputedly began in 15th Century Japan when Shogun Ashikaga Yoshimasa sent his favourite tea bowl, which had been damaged, to be repaired. When it returned it had been mended with metal staples. Of course he could have just replaced the bowl. But he asked the local craftspeople to repair it using glue made out of gold to value and honour the cracks, change, time, wear and tear.

The concept of Kintsugi came from the Japanese aesthetic philosophy Wabi-sabi, which values flaws, irregularities, and defects. This is a beautiful philosophy for living, but also for acting. I believe this quality is what audiences want to see in your work.

THE BEAUTIFUL MESS

These Japanese ideas accord with the psychological theory of the Beautiful Mess, developed out of Brene Brown’s hit TED talk on vulnerability, in which she claims:

We love seeing raw truth and openness in other people, but we are afraid to let them see it in us … vulnerability is courage in you and inadequacy in me.

It is ironic that despite admiring the concept of Kintsugi we still find it tough to celebrate the broken-ness in ourselves, the aspect that makes us unique. Photographer Nan Goldin said:

I knew from a very early age, that what I saw on TV had nothing to do with real life. So I wanted to make a record of real life. That included having a camera with me at all times.

Goldin’s work is full of mess and chaos. She also said about her snapshot approach to photography, in which she explores LBGTQ bodies, moments of intimacy, the HIV crisis and addiction:

I think the wrong things are kept private. By showing the world these things, you can really help people.

She seeks out flaws and errors, derailments and imperfections. It is vulnerabilities that make her captured moments so heartbreaking.

Her work contains humour, tragedy, broken-ness and lightness all at once. In a beautiful production I once saw of Puccini’s opera LA BOHEME, directed by Colin McColl, the theatre design was centred around this photograph. The story of the central character, Mimi and her death from tuberculosis was moved forward in time to the 1980s, the AIDS-era, when this photograph was taken.

VERBATIM

In the rules of Verbatim, the “broken bits”, the “ums” and “ahs”, the jumps, skips and tumbles in the stories the interviewees tell to the writer are reflected in performance, bringing a strong flavour of naturalism. If you watch the films of Chloe Zhou, Debra Granik, Kelly Reichardt and Andrea Arnold, you will see this flavour. They are directors who often cast real people. This is a great challenge for the actors around the real people. The craft of the actor has to seem as submerged and invisible as the lived experience of the real person.

HUMANS OF NEW YORK

There is a close relationship between photography, documentary and verbatim text. They are all re-creations of reality. Brandon Stanton, who created the Humans of New York project says:

Humans of New York began as a photography project. Somewhere along the way, I began to interview my subjects in addition to photographing them. And alongside their portraits, I'd include quotes and short stories from their lives.

Your encounter with the real voices, real stories and real lives of verbatim text can change your relationship with naturalism and screen dialogue. There is no arguing with verbatim. You have to be incredibly precise in order to attain the illusion of looseness. It is hard work and high rewards.

SALT, PEPPER AND CHILI

False starts, stammers, repetition, the odd additional word or interruption — these are all elements of naturalism. They reflect the way real people really talk. You can gift this slightly broken quality to any text. I call this salt and pepper, making it your own by adding seasoning to the meal that has been served to you on the page. You could even add a bit of chilli in the form of swear words.

But remember — for the Shogun’s Japanese tea bowl to be broken, it had first to have been beautifully made. You need to know your text off by heart, and only then can you break it down to make it your own. Not all directors want the text to be negotiated. Sometimes writers want exactly what is written on the page — like David Mamet, Aaron Sorkin, M Night Shyamalan or Shakespeare. They have written precise poetry that they want to hear reflected back exactly as they heard it in their mind. You have to respect their vision, their choice of words, the rhythms, the punctuation. Because words are powerful. As Tennessee Williams wrote in his play Camino Royale:

The violets in the mountains have broken the rocks

PUNCTUATION + BIG PRINT

Punctuation is powerful too. The punctuation dictates the structure of the text. Sometimes when I am working with actors, I will re-type the whole scene and take out all the punctuation and all the big print to see how the rhythm and flow might change without them, revealing new meanings, swirls and eddies. Of course, it’s important to keep the original script as well, that is your ground zero, your core document. This simple exercise can reveal insights and ideas that can help you make the role your own.

Here’s an example of the power of punctuation and the rhythm it dictates. It’s from the book 100 Ways to Improve Your Writing.

This sentence has five words. Here are five more words. Five word sentences are fine. But several together become monotonous. Listen to what is happening. The sound of it drones. It’s like a stuck record. The ear demands some variety.

Now listen. I vary the sentence length and I create music. Music. The writing sings. It has a pleasant rhythm, a lilt, a harmony. I use short sentences. And I use sentences of medium length. And sometimes when I am certain the reader has rested I will engage him or her with a sentence of considerable length, a sentence that burns with energy and builds with all the impetus of a crescendo, the roll of the drums, the crash of the cymbals… sounds that say listen to this. It is important!

THE STUDIUM AND THE PUNCTUM

For the French writer and theorist Roland Barthes the studium in a photograph is the element that initially gets your attention. It is what the photo is supposed to be about.

But the punctum is how he describes the thing that "pricks or bruises." It's that tiny, unintended detail that makes the viewer feel something.

In the world of acting, the punctum is the glorious mistake that happens during a scene, the moment you could not have planned but that you find joy and life in as you ride the wave.

After all, as Miles Davis said:

When you hit a wrong note, it is the next note you play that determines whether it’s good or bad.

It is a paradox that you can only revel in the glorious mistake, in freedom and wildness when your preparation has been meticulous.

Let’s end with some wisdom from the music of the universe:

One of the basic rules of the universe is that nothing is perfect. Perfection simply doesn’t exist. Without imperfection, neither you nor I would exist.

— Cosmologist Stephen Hawking.

REFERENCES

DIFFERENT EVERY NIGHT — Mike Alfreds 2007

100 WAYS TO IMPROVE YOUR WRITING — Gary Provost 1985

TED talk: The Power of Vulnerability — Brene Brown