HOW TO LEARN LINES

"I discovered that my memory is not faulty, I’d just never been taught how to use it"

Welcome back! This is a great interview about how you can hone the skill of learning lines in a way that enhances your performance too.

Each fortnight I publish a free article like this one, and also a paid subscribers’ one. In the paid subscribers’ articles there are even more stories, tips, tricks and tools for actors and directors plus access to an archive of more articles... so if you would like to become a paid subscriber, please check it out here!

“How do you learn all those lines?!”

Any actor will have heard this question. And actually, it is a great question to ask yourself. How you learn your lines is the foundation for everything in your performance.

Your freedom in space, your imaginative universe, your connectivity with your scene partner, your ability to change your offer... all these are directly related to how you learnt the text in the first place.

For this article I am collaborating with Sydney actor Gerard Carroll, who has been on an incredible journey with his approach to text and his relationship with learning.

The video document at the core of this article is a performance by Gerard of a verbatim monologue. He plays a character called Smokey who features in Alana Valentine’s Verbatim play DEAD MAN BRAKE. You can watch Gerard’s three-minute excerpt here.

I have often invited Gerard to bring this incredible character, Smokey into my classes at AFTRS (the Australian Film, Television and Radio School) in Sydney; and to the HUB, an actors’ centre in Sydney. Smokey is a living embodiment of my tools Internal Landscape, Vista, Connection, Journey and White Space. Gerard has taken them onboard and used them to craft this performance of exquisite precision and flow.

He has used these tools to deal with actors’ fear, and to increase his ability to clear his mind, to focus and to achieve actors’ flow.

He has performed this monologue in many different rooms and environments. Whatever the venue, Gerard always finds a way for Smokey to feel vivid, present and connected. He uses vista to ground Smokey in each new place. He has built an internal landscape to achieve effortless ownership of the images his character describes. And in this direct-address monologue he is able to truly connect with each listener.

The key idea here is that Gerard has used an aural approach to focus-on and hear the other actors’ lines — so that he is listening for a cue or a new inspiration rather than thinking about his own text. You will read more about this approach below when he talks about the Dictaphone approach.

He uses an internal landscape to create images that support his text in a flow of thoughts.

He has used a location approach which values the here and now and grounds him in space.

And he has added a time-management tool called the Pomodoro Technique.

Gerard asked me if he could record his thoughts as a verbatim piece rather than writing them down. That exactly reflects the relaxed, naturalistic style that Gerard always aims for in his work. So here is a transcript of Gerard’s thoughts about learning and embodying text. Thank you Gerard!

ACTOR GERARD CARROLL talks to MIRANDA HARCOURT

GERARD: Like I say, I met you just prior to DEAD MAN BRAKE. I’d had a casting for a part, and partly because I didn’t have enough time to know that script well enough, I literally forgot everything. The network people were there, and they threw me in with another actor and I completely dried. My attention was on all the other people in the room. I didn’t know at the time the whole notion of attention; and that it could only be in one place at a time. I left that casting shocked, like I’d been in a car accident, seriously doubting my memory. To the point that I went to my doctor and questioned whether I should have tests done on it.

But then I met you. And I got cast in this show DEAD MAN BRAKE. Out of the blue, the script came through. There were massive chunks of words. And I was bloody terrified in many ways. So, the way I approached it came out of what I’d heard you talk about in that very initial class we’d done. You talked about dictaphones. And I recall at one point in the class, you were just talking and you broke into a verbatim character from, I can’t recall what it was from, but you just started talking — it was so shocking that you went from Miranda instantly to this other person, no notion of taking a breath or preparing. It just happened instantly. It was jarring and so intoxicating at the same time. I could see how valuable that was. So, when DEAD MAN BRAKE and Smokey happened, I bought a dictaphone like you showed me — with a speaker on it — like you’d shown me. I started recording the words on it. And I discovered that my memory is not faulty, I’d just never been taught how to use it.

I met you in 2013, before I did DEAD MAN BRAKE, Alana Valentine’s verbatim play. I did one of your half-day masterclasses at Equity. You’d given us just a few words to say, that’s all we had to do. Before I talk about my process, let me just say that I quickly realised in that class you were teaching things I’d never seen taught in a class before. I could really see the value in it. I could also see that you spoke to every person in that class of 20 differently. Which I’d also never seen. In all my years of Drama School most of the teachers there were so fixed. They had their way of teaching and if you didn’t fit into that, the problem was with you. As a young man who was trying to grow up, I didn’t know how to question those things, I just thought that if I couldn’t learn what they were teaching me, the fault must be with me. I suppose I saw for the very first time, with you, what a really high-quality teacher could do. You flexed yourself with the student as opposed to forcing the student to fix themselves. And now it just seems ridiculous these days a teacher would even try and do the older style, but it still happens. When I was coming out of Drama School in the early/mid 90s that was still the dogma. That set me up for many ways in not having confidence in my own instincts.

I believe it’s assumed actors have good memories. I’m not sure memory is ever taught. Might have changed. But it was never taught when I was training. Even today with casting agents sending out stuff with short time frames I think there’s a real misunderstanding of how memory works for actors. I’m sure there are some actors that can put something to memory quickly, but there are very few of them. I think it goes back to that thing of having your attention on one thing at a time.

So now, if I’m put on camera with only 24 hours’ notice and 3 or 4 pages of script, my attention is only on that, just trying to recall the words. These days, if I get a call for an audition, I use Dictaphone and Pomodoro techniques (see below).

PUNCTUATION

Actually, now I even do this on prose-written plays — I’ll take all the punctuation out — put a stroke through them, cross them out to turn it into a verbatim-style script. Because real people don’t speak in sentences. My aim is to make a structured, written script, which is not verbatim, sound like it is verbatim. That’s the ultimate goal now, to make it sound like a person talking. For DEAD MAN BRAKE I had an hour and a half by train to and from rehearsals. Coincidentally, the train trip went the exact same route that the accident in the play happened. So, every day, as I was going through the script, I was seeing the actual location and environment I was talking about. I’d sit down, put the earphones in and go through listening to the script, using my dictaphone, slowly. And eventually within like ten days of doing that every day I’d turn up to rehearsal and I knew it all. The rest of the cast didn’t at that point, as it was very challenging text to learn. It happened by assimilation and the rest of the cast were shocked, they thought I’d done something magic. And I hadn’t. I’d just done something you’d pointed out to me in a class, using a dictaphone to learn my lines.

So, here’s what I do. I put all the lines down on the dictaphone. If it is a dialogue scene I record the other person’s lines, consecutively, no gaps; and I use the pause button to pause it when it gets to my bits. If it is my monologue, I record it all and listen back to it phrase by phrase, repeating, building and learning.

For DEAD MAN BRAKE, because it was a monologue, I went through it slowly first, like the dropping-in process, word by word.

Then I recorded the whole thing onto the Dictaphone. And then I just methodically and very slowly listen back to each sentence.

Now, people might think that when I say dictaphone, “Oh, OK he just means using an iphone line-learner app”. But no, let me clarify that looking down at a touch-screen constantly is very different from pressing a manual button without having to look at the device. I mean an old-school, analogue Dictaphone!

REPETITION

It is a bit of a dogma amongst some actors, to keep things fresh. They are scared that repeating text will kill it. But my experience is it makes things deeper, wider and bigger. We seem to be fed the notion that repeating things too much will make it stale. My experience is that — if the material is good to start with — it will just improve.

This exploration was driven by my terror of ever drying again in an audition or on a stage. Panic became a driver, that forced me to repeat things. A lot.

During DEAD MAN BRAKE, I went over it so many times. I didn’t keep a score or make a count but I just know it was A LOT! I wanted it to be viscerally in my body. I wanted to never have an image in my head of a word on a page.

Initially, I didn’t really have a structured way of approaching this learning, I would just go and go. I’d lock myself up for hours and hours and do it. And that’s not very healthy. Before DEAD MAN BRAKE went on stage, I got it to a point where I could walk in the park with my Dictaphone — which I would use to reference a part of the script if I forgot it — as I was walking and speaking out. That locks into that thing you taught me about VISTA, particularly in relation to the Smokey character, the character could exist anywhere. If I’m walking through the park, then I’m Smokey in the park. In the video link I sent you, I’m telling the same story sitting in a chair in a room, so Smokey is sitting in a chair in a room. I felt the benefit of that style of learning.

And I thought it was a good thing for me to keep these pieces alive. Particularly with the verbatim stuff. So, I’ve kept all these pieces alive over the years. Very occasionally, if I haven’t done it for a couple of months, I might drop one of the thoughts and so then I’ll look at the script to check. But to be honest I don’t like seeing the words anymore because I know each phrase now as a thought and a sound.

POMODORO TECHNIQUE

When I really got this approach really structured was when I was cast in the play PROOF by David Auburn.

I played a mathematician. My role was a re-cast, the other three cast members had done the play before and so I was joining them. So, I had a seven-day lead-in and then a five-day rehearsal before opening the play. A chance conversation with my sister-in-law, who isn’t an actor, suggested I use a study method called the Pomodoro Technique, it’s Italian.

The fellow who developed it had an egg-timer shaped like a tomato (which is “pomodoro” in Italian) and he would study for 20/25 minutes strictly. Stop. 5-minute break. Do nothing or have a total break from the study. I could see that I only had a seven-day lead-in and I would just have to structure it. I was put onto this Pomodoro approach and it was so liberating. Twenty minutes study at a time then stop. Do a couple of hours of those, then a 30-minute break. So, for PROOF, I slowly did that, dropping in the whole script and using the dictaphone. I just took it really slowly. In that seven days, I’d take my dictaphone to the park with all the other characters’ dialogue on it and I would speak my lines in response to my own recorded voice speaking out their lines. And, this is important, when I was recording the material to begin with, I would NOT leave pauses for my own lines. Instead, I would use the pause button to give myself as much un-pressured time as I needed, to respond to the cue with my own line.

When I hit the first day of rehearsal I knew all the dialogue and all the other actors were both very appreciative and shocked. So that’s the technique I use now — short bursts of study.

The dictaphone trains you aurally. The listening aspect triggers the creation of pictures, not only the learning of your own words. Also, the simplistic beauty of Pomodoros, is that they are brief and very focussed. You don't want to be checking phones alerts/messages. The Pomodoro/dictaphone is, by default, training you to have prolonged concentration without distraction. A skill that is waning.

DISCOVERING CHARACTER

I was always interested in people’s real voices, but perhaps I didn’t always notice that how you sound and speak is who you are, in so many ways. All that psychology they try to get you to create for a character prior to doing it, is unnecessary. If you can approach it the other way — the sound of the person, the “voice” of the person — that work is done for you. We listen to people speaking on the street and we’re struck instantly by an idea of who they are. It is not because we have an insight into their psychological motivations, it’s because we have heard their voice.

I still find when I go to classes, most of it is tending towards motivation of the character, objective and psychological drives. To be honest, that’s never worked for me. One of my worst hates is when I’m rehearsing a scene and I don’t know what it’s about yet, and the director asks, “What do you think your character wants in the scene?” And I hate it, because 1) I don’t know yet; and 2) it’s really of no consequence to anyone else! If the director trusts me enough, I’ll have a chat with them before and ask them not to do that because it doesn’t work for me. I have to go a different way, I think it might be the same for a lot of people. That approach of doing table-reads and sitting for days and days and breaking a unit to beats and motivations does not work for me.

But when I’ve learnt verbatim monologues — particularly with an accent or dialect — it has triggered thought processes and physical things in my body, which have happened of their own accord, I couldn’t do that myself from scratch. Actually, it was interesting with Smokey, Alana the writer-director wouldn’t let me hear the audio recordings. I wasn’t happy about that at the time. She thought we might just copy. I think copying is often undervalued. I think sometimes if you copy a person’s voice you subliminally imbibe who they are. I’m not just talking caricature — a good actor can viscerally understand that person from within, it’s more than just copying a voice. Well, she wouldn’t let us do that. But the weird thing was I met Smokey on the opening night of that play, which was intense — and we sounded a lot alike. My physical movements were similar too — that’s when I realised that those physicalities in your body are linked to voice. All I had had were the words and that had forced the physicality. That is a lesson that sticks with me to this day.

VALUE OF VERBATIM

The value for all actors to learn verbatim stuff is the way it functions differently to prose (written text). At acting school there was a reverence to full stops and commas that drove me insane. Still does. Often characters in regular plays are too cogent, too self-aware of their own mental processes. As you know, even from this recording-transcript you are reading right now, we turn and twist conversationally, we flick between past, present and future, sometimes they’re existing at the same time — and that’s real life. That’s why I think the Smokey thing is so easy to do and so good to watch.

That’s the value of getting an actor to learn a verbatim monologue. Tear out the psychological motivation and just learn it — see what happens, where it takes you. A verbatim monologue of any length will do all those things — flip between past, present, future, self, self-reflection, other points of view, talking in third person — all those things we do in real life. In a conventional, structured script, people don’t do that. Though these days, a modern scriptwriter might write in the verbatim style. I did a play at Ensemble Theatre with Genevieve Lemon about two years ago (FOLK by Tom Wells) set in a small town on the East Coast of England, really specific East Yorkshire accents.

For that character, I found a person on YouTube, a farmer, and I stole his voice essentially. It made my work easier on that character, I still had to learn the words, but it was written hinting toward a verbatim scenario. By learning verbatim pieces I’ve become accustomed to learning broken thoughts, I find it liberating. Difficult up front, but once you do learn it, this approach lets you fly on top of the text.

ANTHONY HOPKINS

I think we’ve talked about procedural or episodic memory before.

That’s where Smokey sits for me now. If you’re given two days to learn a script it can’t sit in that semantic part of your memory. It needs to be in a flow state where you can just pull it out.

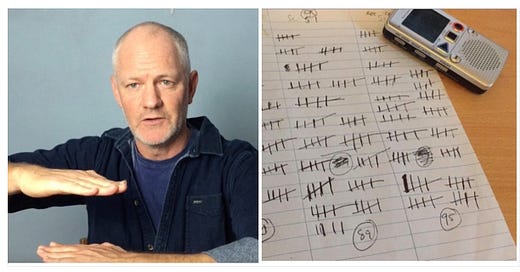

I only got it from you — and it could be urban myth, that thing about Anthony Hopkins saying that a script’s not in his body until he’s repeated it two hundred times. That’s interesting for me now, I know that to stand up in front of people and do a performance or like that piece I sent you the other day, I had about six days to prepare that, so I spent the first five days learning it. I know that to make it look effortless, I have to do it about one hundred times. So, I think for that I actually learned and repeated it about one hundred and thirty times. So, the thing with the Anthony Hopkins approach, I sort of play with that now, and I keep a tally when I’m going through pieces of how many times I have done them. A lot of that is predicated on whether you’re given enough time to do that!

Time is really the big factor for creating images and for that mental growth to happen. The 200 x Anthony Hopkins Repetition Thing is a game I play with myself now. I try to do it as much as I can. That makes me do the work, and when I’m in a rehearsal room and other people haven’t done it, I’m aware of the differences I can hear. By that stage, I’m recalling images. Ideally, it’d be best if everyone was at the same stage, but often the other actors don’t get to that until the end of week one of the performances. Whereas my aim is to get to that experience much earlier.

I’ve discussed with you before how much I dislike the word “text”. Every time I hear that word I think of dots and lines on a page... and what I’m trying to do is get to the antithesis of that.

THANKS TO

Gerard Carroll

Alana Valentine

Simon Sweetman